Virtual DOM

React components are created using JSX, but the browser has no clue what it is. Browsers only understand plain JavaScript, so somehow JSX will have to be transformed into it. Consider this JSX that is returned from a component.

return (

<div className="title">

Title!!

Paragraph 1

<Button text="submit" />

Paragraph 2

</div>

)

}

When React starts parsing the JSX, it either sees an HTML (div) or React component (Button) and it internally calls React.createElement(). There are only two possible elements inside JSX:

- Plain HTML

- React Component

Inside that function HTML types (div) are passed as string type argument whereas for components (Button), React.createElement() is called. Putting them all together, the function call would look something like this,

React.createElement("div", { className: "title" },

"Title!!",

"Paragraph 1",

React.createElement("Button", { text: "submit" }),

"Paragraph 2"

);

The first argument to React.createElement() is the "div," which has a string type. The next one is the props which has a class name and children. Since Button is a React component, it must be reduced to HTML. For that React calls React.createElement() for that component which would return plain HTML button type.

Now that React has created the functions having arguments holding function calls, objects, strings, etc. How does it all get transformed into DOM elements that form a web page? For that, we have a ReactDOM library and its render method:

ReactDOM.render(

React.createElement("div", { className: "title" },

"Title!!",

"Paragraph 1",

React.createElement("Button", { text: "submit" }),

"Paragraph 2"

), // "creating" a component

document.getElementById('#root') // inserting it on a page

);

First, React would call for div, which is a plain HTML, creating that element. For Button, which is a component, it returns the HTML button type. For a more deeply nested component, React may keep on calling React.createElement() recursively until it reaches the plain HTML type for a particular child, i.e., from the top of the tree to the bottom. Whatever the parent component wraps, either plain HTML or components, they act as its children.

{

type: 'div',

props: {

className: 'title',

children: [

'Title!!',

'Paragraph 1',

{

type: 'button',

props: {

value: 'submit'

}

}

'Paragraph 2',

]

}

}

Now, this resultant object constitutes virtual DOM. This object might be very deeply nested, having thousands of elements.

DOM vs. Virtual DOM

In React, for every DOM object, there is a corresponding virtual DOM object. It represents the actual DOM, but the only thing is, it's not the actual DOM, i.e., it lacks the power of printing anything on the screen directly. React does not mutate the DOM directly; instead, it makes changes in the virtual DOM which are then committed to the DOM. React internally uses the DOM APIs to make those changes.

Since there is a Virtual DOM object corresponding to every DOM object, it allows React to mark the changes in the virtual DOM of a particular element and make direct changes in the actual DOM of that object rather than building the whole DOM again. (More on this later)

Reconciliation

When we make changes on the web page, it must be reflected accordingly. One way to do that is we re-create the whole page with the updated data, but that would be too slow. In the case of React, we have Virtual DOM that React has direct access to. When we make a change in the page (to be precise, if the application's state is updated, more on this later), React would re-create the whole Virtual DOM. Since Virtual is just an object, the process would be quite fast. While creating the new Virtual DOM, React would compare the properties and content of each object with the previous Virtual DOM. While making the comparison, four scenarios might come up:

- type is a string and did not change after the update; props did not change either. Before update

{

type: "div",

props: {

className: "title"

}

}

After update

{

type: "div",

props: {

className: "title"

}

}

Since there are no changes before and after the update, Virtual DOM and DOM would remain the same.

- type is a string and did not change after the update, But props changed.

Before update

{

type: "div",

props: {

className: "title"

}

}

After update

{

type: "div",

props: {

className: "heading"

}

}

Since props have changed, React would remember this change to perform, and it would directly mutate the HTML element using DOM APIs.

- type is a string, and it changed.

Before update

{

type: "div",

props: {

className: "title"

}

}

After update

{

type: "p",

props: {

className: "title"

}

}

Since the type has changed, React will have to delete the older element and all its children and replace it with the new one.

- type is a component.

Before update

{

type: "Button",

props: {

className: "submit"

}

}

After update

{

type: "Button",

props: {

className: "submit"

}

}

React sees that type is the same, and props are the same, so there is no need to update. But here is a catch, components have states defined inside them, which primarily determines the status of the component. If the state has changed, that change must be reflected on the screen. React would have to check the component's states and make changes accordingly.

Let's understand the process with a high-level example. Let's assume that a React component has 100 children. These children are stored in props in the form of an array.

type: "div",

props: {

className: "list",

children: [

{ type: "div" },

{ type: "div" },

{ type: "div" },

//...

]

}

}

Now, this component is updated, and say the item at the 50th index got updated. How would React update it? The most naïve way to think about it would be to compare the array before and after the update and mark the changes. React would compare the 0th index of the previous array with the 0th index of the new array, the 1st index of the previous array with the 1st index of the new array, and so on. And if there is a change at a particular index, it would mark the changes. But that would be very inefficient in certain cases. Let's say that we delete the item on the 50th index, then the item on the 50th index of the previous array won't match with the item on the 50th index of the new array, and so on. Therefore, React will have to update all the items after the 49th index. That update would be a total waste since those further items did not change. To overcome this, React uses a key with every element in the array. The items in the array contain one more property called key. The key must be unique for each element in the array.

{

type: "div",

props: {

className: "list",

children: [

{ type: "div", key: 101 },

{ type: "div", key: 102 },

{ type: "div", key: 103 },

//...

]

}

}

If we delete the item on the 50th index having key 150, React would still know that all elements with the key except 150 were already there before the update, so there is no need to make changes to all those items. We can move around those items without removing or re-creating them.

The old Reconciler (Stack Reconciler)

JavaScript is single-threaded. When the browser executes JavaScript, all other tasks like layout, animations, etc., are blocked. When React creates the component instances or updates them, it keeps on calling the functions recursively until it reaches the bottom of the tree. Calling multiple functions recursively causes the stack to fill with many function calls. The main thread is now burdened with all those function calls. This blocks all other tasks, i.e., no CSS updates or animations stuff could execute. A 60 Hz screen is supposed to re-render every 16ms, and so is the browser. But, since the main thread is over-burdened with functions, it won't be able to call the render function, which would result in the browser dropping the frames (Read more about this here).

In case of Stack Reconciler, once the tree construction starts, it keeps on executing until the whole tree construction is over. As a result of which the tasks that are lying in task queue or microtask queue won’t be able to execute. Even a high priority task would have to sit in the queue. That’s where React fiber comes and solve the problem. It gives React, the capability to pause, resume, abort the tree construction process.

Fiber

A Fiber is work on a Component that needs to be done or was done. There can be more than one per component.

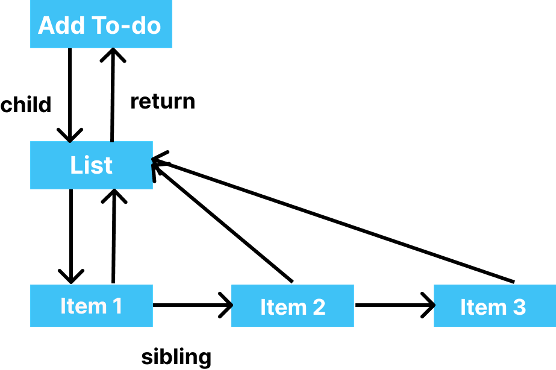

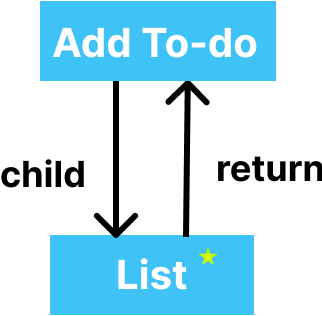

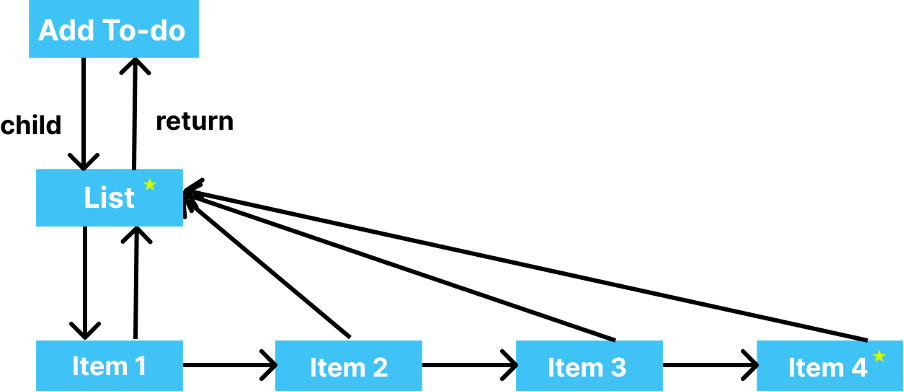

Let's understand this in a simple form. Fiber is a data structure, or even simpler; Fiber is an object which has many properties. You can find the declaration of Fiber here. Fiber has a one-to-one relationship with the instance of the component. It manages the work for an instance. But wait, what work is? Will come to that later. Some properties in the Fiber object are:

- stateNode

- return

- child

- sibling

Let's consider a to-do list having an Add to-do button and a list of to-dos. stateNode points to the current instance it's holding.

React has now divided the update process into two phases:

- Phase 1 – This phase starts constructing the new tree called the work-in-progress tree by continuously tracking the changes that have happened in the old tree. This process is known as a work loop. Whenever it sees that there's a change, it marks that instance in the new tree and remembers it. This phase is interruptible, i.e., the main thread can pause the construction of this tree, can go and perform some other tasks and come back and continue the tree construction.

- Phase 2 – This is the commit phase—this phase is not interruptible. Phase 1 has already marked all the changes that have been made. It has only been marked, and nothing has been reflected in the DOM. When the commit phase starts, React, using the DOM APIs, performs all the changes to the DOM.

How is the Stack Reconciler different from Fiber Reconciler?

Let’s assume that setState has been called and the component must re-render now. There’s already an existing tree and now a new tree will be created.

• The process of creating a new tree in Stack Reconciler is not interruptible. Once the construction of the tree starts, it won't stop until it's finished. Because of this, the main thread would be completely blocked and won't be able to perform any other functions like changes in UI when the browser is resized or CSS animations, etc. The Fiber Reconciler keeps track of the time quantum that it has been allotted to construct the work-in-progress tree. And at the beginning of the new quantum, it releases the main thread and lets it perform the other action. Internally the Fiber reconciler uses requestIdleCallback() to keep track of the idle period of the main thread. This method queues functions to be called during a browser's idle periods. So, this means that work-in-progress tree is created keeping in mind and giving priority to other tasks too that browser must perform apart from creating the work-in-progress tree. This is the reason why the state updates in React are asynchronous. React defers the tree creation giving priority to other tasks to execute.

• Stack Reconciler mutates the DOM as it constructs the tree. It means that before moving to the next element in the tree construction, Reconciler would call the DOM APIs and perform those changes in the DOM. Whereas Fiber Reconciler only marks the changes until the construction of the full tree is over. If any side functions like browser resize happen in between the work-in-progress tree construction and the UI moves around in the page, then those changes that were supposed to be made via state update won't be reflected since they haven't been committed yet. After these changes are committed (which happens in phase 2) then, only those changes would be observed in the DOM.

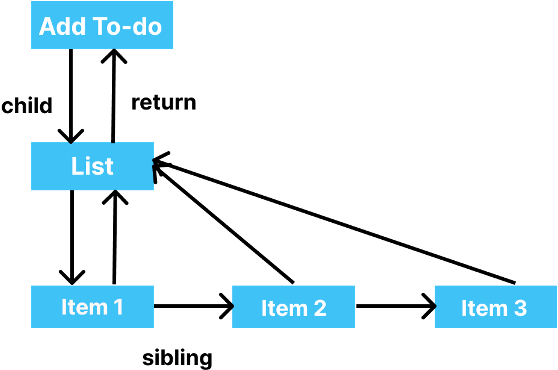

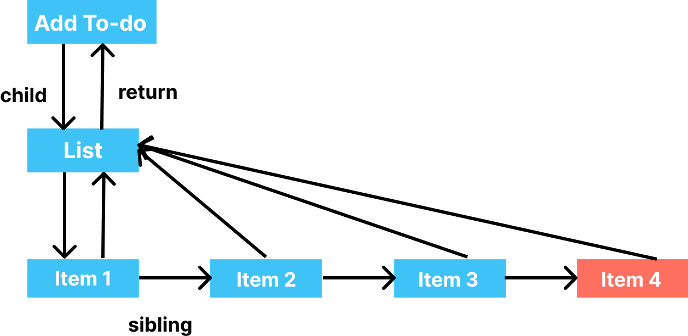

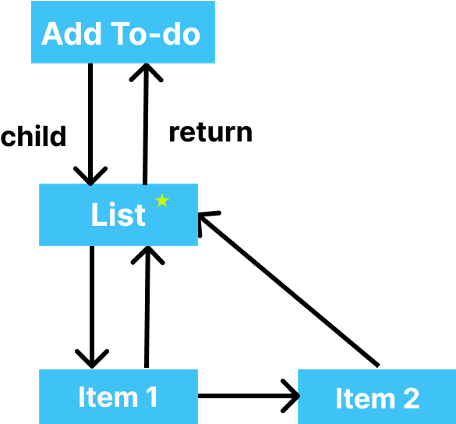

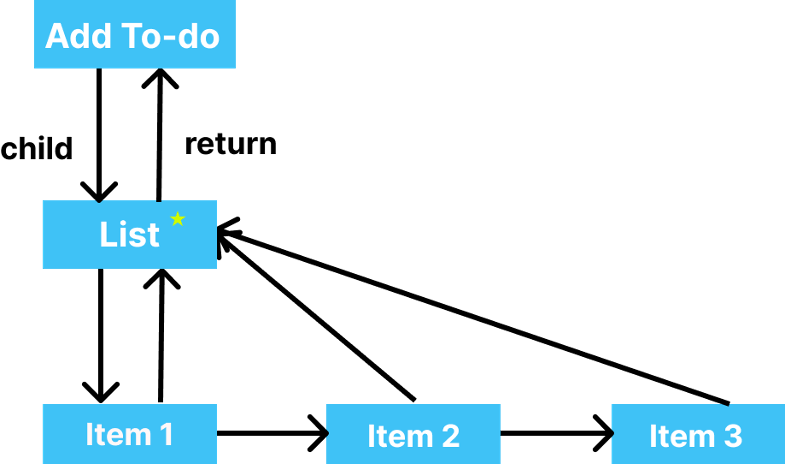

Let's consider a situation in which React has already created the render tree, and everything is displayed on UI. Now, the user adds an item to the to-do list. Adding that item updates the state of the component and causes the component to re-render. Now, React will start building a work-in-progress tree, continuously tracking the changes in the old.

Old version

New version

Now let's see the step-by-step construction of the work-in-progress tree.

Step 1 - React starts with the Add To-do Button, checks the old tree for any updates, and since there are none, it directly clones it. And it checks whether the time quantum has expired or not. Fortunately, it hasn't, so React continues to build the tree.

Step 2 – It moves to the List and sees that there are changes that have been performed, so it marks the List for further inspection.

Step 3 – It enters the items on the list. React checks whether the first item of the List has been modified or not. And since it was not, it clones it from the older tree. Again it checks the time that has left and finds that there's no time left, so now it releases the main thread and allows it to do the other tasks (if any).

Step 4 – After doing some other tasks, the main thread is back and ready to continue the construction of the tree. React moves to the next item in thirst and, after comparison, finds that again, no changes were made, so again it simply clones it.

Now, the user tries to resize the browser. It has a callback associated with it which is stored in a queue. This callback need not be executed immediately. Since React still has some time left with it, it could continue the tree construction.

Step 5– React does the same thing with the next item in the List. Since it has no changes, React clones the item.

Step 6 – Moving toward the next item in the List, React sees that no such item is present in the older tree and thus adds it to the work-in-progress tree and marks it. Then React checks for the time remaining and finds that no time is remaining.

Now React releases the main thread. There is already a callback queued from the browser resize that the main thread must execute. The main thread executes that callback, but item 4 is still not added to the DOM. This is because the changes have not been committed yet to the DOM. After the main thread executes that callback, it comes back to React and since the tree construction is over, so React now places all the nodes to be changed in an Effect List.

React now starts committing those changes to the DOM. This process is not interruptible else; it takes the UI into an inconsistent state. While committing those changes, React calls the DOM APIs to directly mutate the DOM and reflect those changes in the UI.

Fiber has given React the power to break down the tree construction (which is a big process) into small pieces of work and build the tree in an asynchronous manner giving other tasks some time to execute.

Fiber Reconciler is pluggable i.e., it can be combined with any renderer (ReactDOM) to print something on the screen.