PermalinkWhat is a callback function

A callback function is a function that is passed as an argument into another function and invoked by the outer function either synchronously or asynchronously.

PermalinkNeed of callback function

JavaScript is a single-threaded language. It can only execute code sequentially in top-down order. But there are instances where a specific code must execute only after a certain event (like fetching data from the server) has already happened. The APIs handling asynchronous events are designed to accept a callback function as an argument, and only when that asynchronous task has happened, they execute the callback function.

PermalinkSynchronous callbacks

const words = ["callbacks", "in", "javascript"];

function mapCallback(word) {

const upperAlphas = word.toUpperCase();

return upperAlphas;

}

const result = words.map(mapCallback)

console.log(result) // [ CALLBACKS, IN, JAVASCRIPT ]

function mymap(array, mapCallback) {

let newArray = [];

function forEachCallback(item, index) {

newArray.push(mapCallback(item));

}

array.forEach(forEachCallback)

return newArray;

}

const newArray = mymap(words, mapCallback);

console.log(newArray) // [ CALLBACKS, IN, JAVASCRIPT ]

function filterCallback(item) {

if (item !== "javascript") {

return item;

}

}

const filteredArray = words.filter(filterCallback)

console.log(filteredArray) // [ callbacks, in ]

The most common usage of the synchronous callback function is with the Array methods. E.g., map(), filter(), reduce(), forEach(). As shown in the above snippet, we call map() on the words array and pass the mapCallback function. The map function internally calls the mapCallback for each element in the array, and it passes that element as an argument. However, we don’t know how and when the mapCallback is executed by the map as its internals is hidden from us. We completely trust that map would call our mapCallback for each element in the array, and surely it does, so no issues. A similar case happens with the filter method. The mymap function tries to mimic the execution of the map function. Since we wrote it ourselves, everything is visible to us, like how and when it is called internally, and we can trust it completely as we wrote it. (Of course, there would be multiple checks and all in Array.map() and it's more secure).

PermalinkAsynchronous callbacks

function setTimeoutCallback() {

console.log("Executed after 3000ms");

}

setTimeout(setTimeoutCallback, 3000);

function setIntervalCallback() {

console.log("Executes every 3000ms");

}

setInterval(setIntervalCallback, 3000);

setTimeout takes the callback function as an argument and the delay after it will be called. setInterval also takes the callback function as an argument and the interval after which will be called again and again.

function httpFetchAsync(url, httpSuccessCallback, httpFailureCallback) {

const xmlHttp = new XMLHttpRequest();

xmlHttp.onreadystatechange = function () {

if (xmlHttp.readyState == 4) {

if(xmlHttp.status === 200) {

httpSuccessCallback(xmlHttp.responseText)

}

else {

httpFailureCallback();

}

}

}

xmlHttp.open("GET", url, true);

xmlHttp.send(null);

}

httpFetchAsync(url, httpSuccessCallback, httpFailureCallback);

The HTTP request is the most obvious use case when discussing asynchrony; the httpFetchAsync accepts httpSuccessCallback and httpFailureCallback, which is called depending upon whether the request was successful or failure. These callback functions are not called with the flow of code; instead, they are called at a later time in the code execution, which might be even after the garbage collector has removed httpFetchAsync. The role of browser API and Event loop comes into the picture when discussing its internal mechanism. (More about them in the upcoming blogs).

PermalinkProblems with callback

There is a famous phrase, “callback hell,” that has been termed after the shortcomings of the callback function.

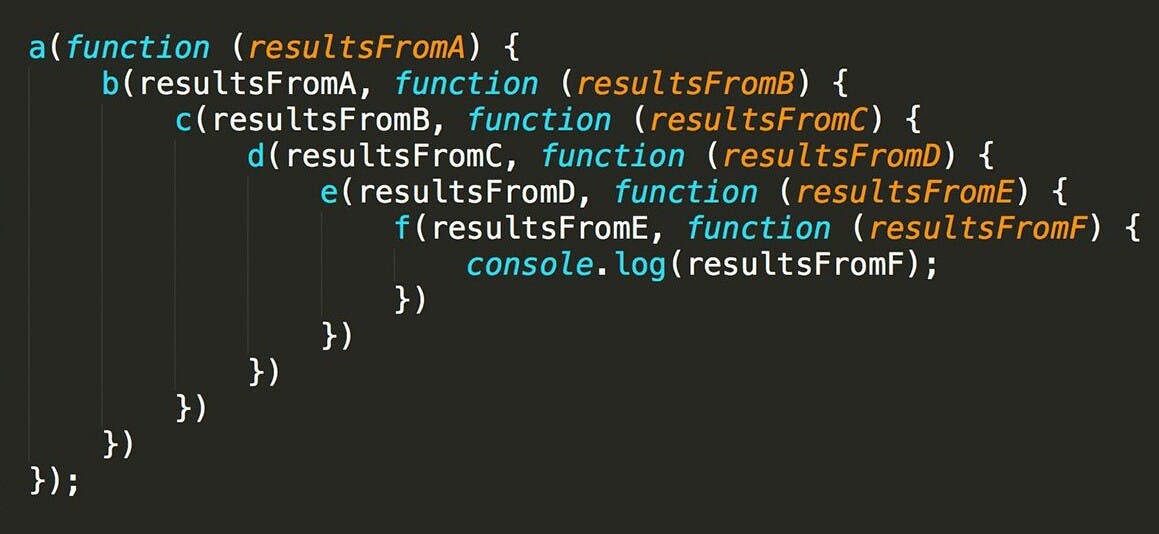

PermalinkNested callbacks

When the callbacks are deeply nested, there’s a lot of eyes jumping through the code snippet to understand its execution. The overall readability of the code reduces. A deeply nested callback function could look something like this,

PermalinkBrittle code

Since these callbacks are executed one after the other, In the above code, what if a specific function fails to execute? If that happens, the following functions won’t execute. And to handle errors, the error handlers must be hardcoded into the function. But, it makes the entire code brittle, and there would be a lot of boilerplate code to be written to execute tasks. Overall reusability of the code would reduce and would become very hard to maintain. Thats why the "callback hell", but there's more.

PermalinkThird party libraries

There is always a potential threat to our code when we rely on 3rd party packages. Even though the API guarantees the proper execution but what if the callback is never called, what if the callback is called multiple times, what if the parameters are not passed correctly, what if the API swallows the errors generated, how would the function retry if the execution has failed, etc.? To avoid such incidents to some extent, we need to put a lot of defensive checks in our code.

A great example of a potential threat by a 3rd party API Tale of five callbacks - by Kyle Simpson.

So, to resolve all these issues, the developers of JavaScript came up with Promise, which we all use today. More on Promise in the upcoming blogs.